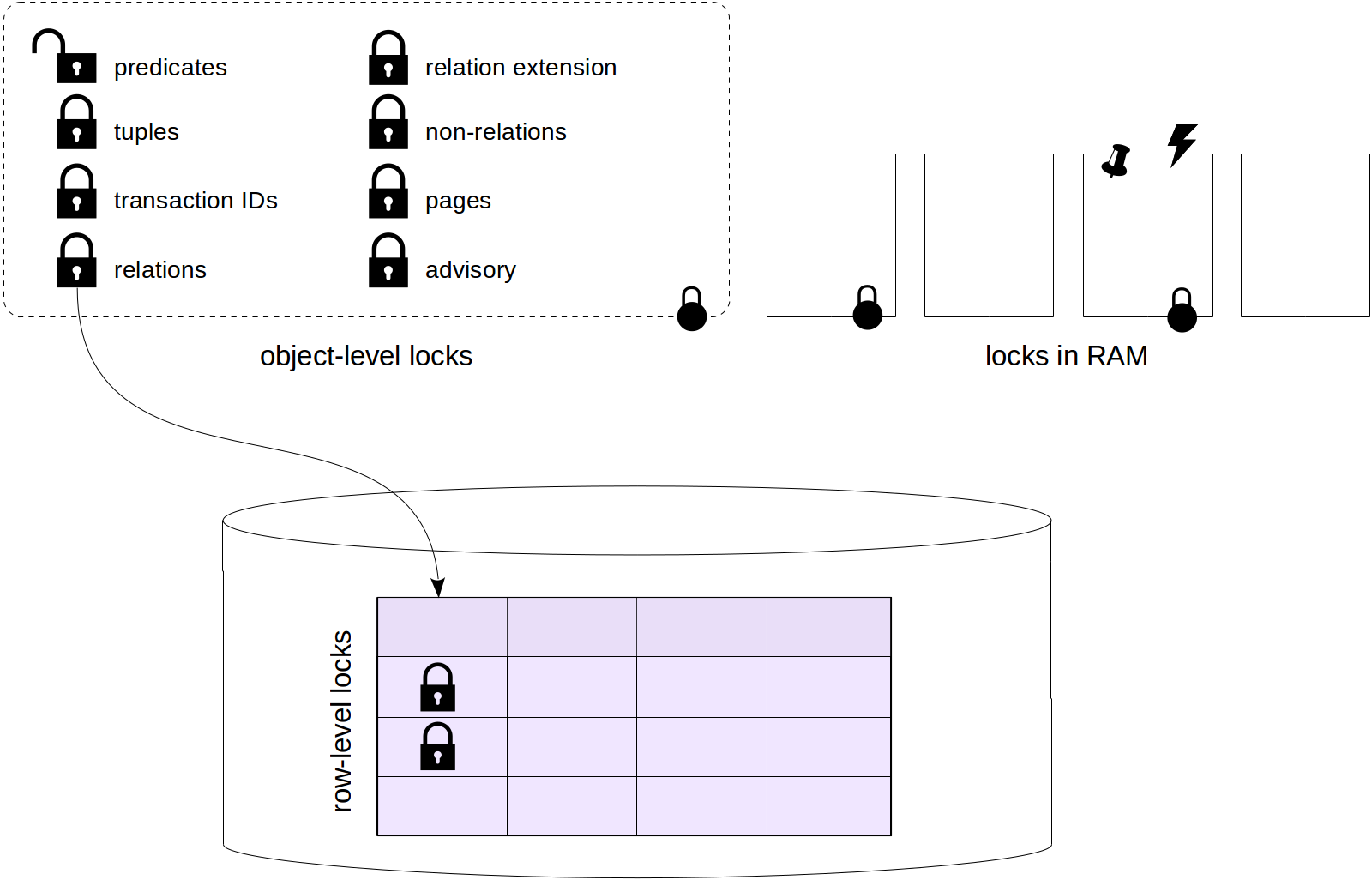

We started with problems related to

isolation, made a digression about

low-level data structure, then discussed

row versions and observed how

data snapshots are obtained from row versions.

Last time we talked about HOT updates and in-page vacuuming, and today we'll proceed to a well-known

vacuum vulgaris. Really, so much has already been written about it that I can hardly add anything new, but the beauty of a full picture requires sacrifice. So keep patience.

Vacuum

What does vacuum do?

In-page vacuum works fast, but frees only part of the space. It works within one table page and does not touch indexes.

The basic, «normal» vacuum is done using the VACUUM command, and we will call it just «vacuum» (leaving «autovacuum» for a separate discussion).

So, vacuum processes the entire table. It vacuums away not only dead tuples, but also references to them from all indexes.

Vacuuming is concurrent with other activities in the system. The table and indexes can be used in a regular way both for reads and updates (however, concurrent execution of commands such as CREATE INDEX, ALTER TABLE and some others is impossible).

Only those table pages are looked through where some activities took place. To detect them, the

visibility map is used (to remind you, the map tracks those pages that contain pretty old tuples, which are visible in all data snapshots for sure). Only those pages are processed that are not tracked by the visibility map, and the map itself gets updated.

The

free space map also gets updated in the process to reflect the extra free space in the pages.